By Dan Murphy

I loved baseball growing up as a kid in Northern Westchester, and I was a Yankee fan, but I enjoyed watching and learning about all the great players and their statistics that made up a Baseball Encyclopedia.

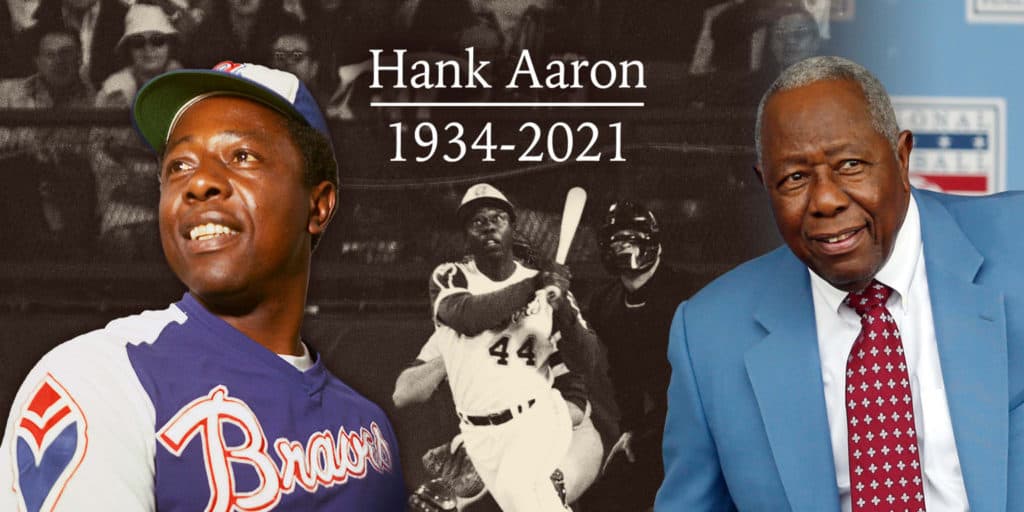

The biggest and most important baseball statistic and number was 714, which was the number of Home Runs hit by Babe Ruth. That was until April 8, 1974 at Fulton County Stadium in Atlanta, when Hank Aaron hit #715.

That video has been played repeatedly this past week after Aaron died at the age of 86 on Jan. 22. That clip I watched live with my family as a 7-year-old. The game was on national TV and although I loved the Yanks and the Babe, I admired Hank Aaron for hitting 715 home runs.

He is the Home Run king fair and square, I thought. Little did I know how much racism and hatred Aaron had to go through to hit that home run.

Henry Louis Aaron was born in Alabama in 1934 and was raised in the segregated South. He joined the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 and played there until the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966. Aaron wasn’t thrilled about returning to the south during the Civil Rights movement. “I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again. We can go anywhere in Milwaukee. I don’t know what would happen in Atlanta.”

Hank Aaron admired Jackie Robinson and often said that “I was carrying on where Jackie Robinson left off. I believed, and still do, that there was a reason why I was chosen to break the record,” he wrote in “I Had a Hammer.”

I listened to WFAN sports radio the day after Hank Aaron died, and former Yankee Rick Cerone recalled an event from 1980 held in Yorktown Heights at Huckleberry’s restaurant, to promote a magazine that Cerone had helped create called “Baseball Magazine.”

A lunch was held for the baseball team of the decade. Aaron was named the right fielder of the 1970’s and attended the lunch. Later on, Aaron’s 715th Home Run was named the biggest baseball event of the 1970’s by Baseball Magazine, and a press conference was held in New York City to help promote it. The Commissioner of Baseball, Bowie Kuhn, was going to attend and hand out the awards to several baseball starts including Aaron.

On the day of the press conference, Aaron sent a telegram explaining why he couldn’t attend. “I understand that Mr. Kuhn requested that he present me with the award for the outstanding moment of the 1970’s, in honor and recognition of the new all-time home run record set on the eighth of April 1974. However, looking back on that time, I remember the commissioner did not see the need to attend,” wrote Aaron in his telegram.

Kuhn had a prior engagement that day, to speak before the Cleveland sports club. Kuhn was in attendance when Aaron tied Babe Ruth with homer #714, but in a bad decision, didn’t cancel to get to Atlanta to see #715. And Hank never forgot it and never let Kuhn forget it.

“I do think that for me to be there in 1980 to accept an award from someone who in 1974 didn’t feel he had to be present would have been a direct slap in the face,” said Aaron to the New York Times. “It was a slap in my face and a slap in the face of the fans in Atlanta in 1974 when the Commissioner didn’t attend the game in which I broke the record. I hope the Commissioner didn’t think I was going to forget about it.”

Aaron also said in the telegram in 1980 that he was disappointed in the lack of former black baseball players being hired in the front offices of baseball teams and major league baseball.

The headline from the Chicago Tribune after Hank hit #715 in 1974 was “Hank Hammers it home!” Reporter John Husar also noted, “commissioner Bowie Kuhn sullied the office by declining to attend the game, sending Monte Irvin as his representative. The mere mention of Kuhn’s name during the commemoration ceremonies elicited over a minute of booing.”

In the days and months before hitting #715, Aaron received numerous death threats that if he broke the Babe’s record, he would be killed. The Post Office noted at the time that Aaron had received more mail than anyone who was not a political figure, most with letters warning him “I have a contract out on you, and “My gun is watching your every black move.”

“The Ruth chase should have been the greatest period of my life, and it was the worst,” Mr. Aaron wrote in his 1991 autobiography, “I Had a Hammer.” Aaron’s friend and baseball great Billy Williams said, “He was breaking an icon’s record, a man who was white who was idolized for so many years. How was Aaron able to continue with threats to himself and his family? “He dealt with it, and maybe it made him more focused, and more determined,” said teammate Dusty Baker.

Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully spoke for most of America when he said on the night he hit 715, “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

The accolades for Hank Aaron poured in from across the country in memory of his passing. “We have lost one of America’s greatest athletes, Hank Aaron who broke Babe Ruth’s home run record in 1974. Some white citizens hated him because they didn’t want black Aaron to beat the white Babe’s record. Bless Hank, he inspired so many of use but let us remember that this kind of racial hatred still exists,” said Colin Powell.

Dr. Bernice King, daughter of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “I am deeply saddened by the passing of baseball legend #HankAaron. Like my father, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he stood strong against hate and racism and was able to persevere, becoming one of the greatest baseball players that has ever lived. My father was a big fan of baseball and of Mr. Aaron. He and my father shared a mutual respect and admiration. After the assassination of my father, Mr. Aaron was very supportive of my mother, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, and The King Center,”

Magic Johnson tweeted, “Put Aaron on the Mount Rushmore of Baseball GOATS!” I would agree but that is tough Mount Rushmore to come up with for baseball players, but the Babe and Hank Aaron is a good place to start.

Quarterback Drew Brees said, “Hank was a true legend who can never truly leave us. Legends teach us how to live and be great like them.”

When he joined the Milwaukee Braves in 1954, Aaron became active in the Civil Rights movement. He helped John F. Kennedy win the Wisconsin primary in 1960 and Bill Clinton win the democratic nomination in 1992.

In 2001, Clinton presented him with the Presidential Citizens Medal for “exemplary service to the nation.” In 2002 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush.

Aaron remains first in the major league history in runs batted in (2,297) and total bases (6,856) while ranking third in hits (3,771). But he is no longer the “official” home run king.

That is because Barry Bonds surpassed Aaron in 2007, but he did so with the help of steroids. We agree with Reggie Jackson, who called Hank Aaron, still, “the people’s home run king.”