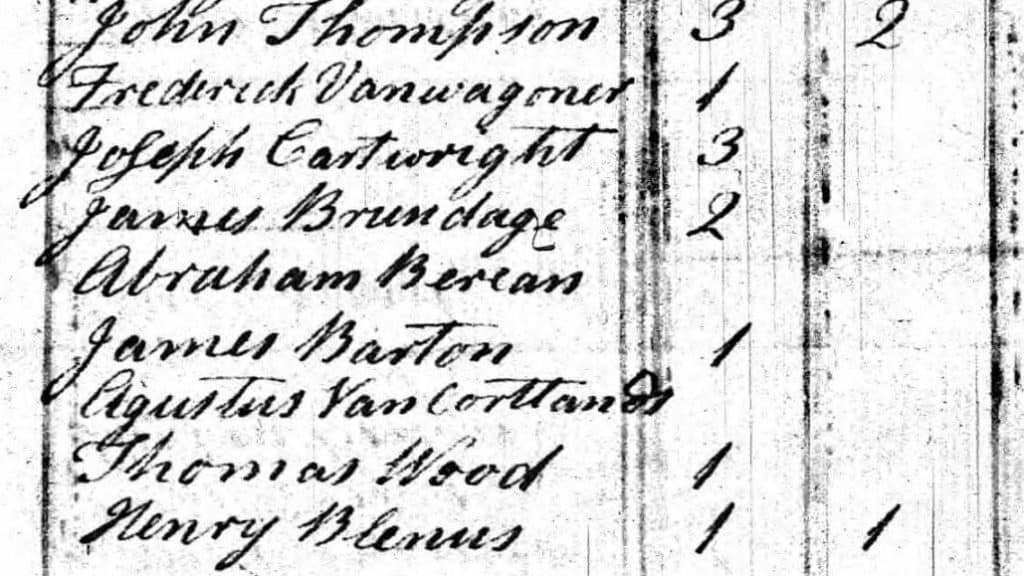

1810 Census showing residents of Yonkers

By Dennis Richmond Jr.

A conversation about slavery is never easy. It is an open wound, a reminder of a past too often sanitized or ignored. The truth is, slavery was not confined to the sprawling plantations of the South. It was everywhere. It was in the cobblestone streets of New York. It was in the quiet corners of Yonkers. It was in the names we see on street signs today—remnants of a time when human lives were bought and sold, right here, in our own backyards.

When we think of slavery in America, we picture vast cotton fields stretching into the horizon, where Black men, women, and children toiled under the unforgiving sun. But in Yonkers, slavery looked different. There were no sprawling plantations, no endless rows of cotton. Here, slavery existed in the homes of everyday people. A merchant. A craftsman. A family. Some slave owners held only one person in bondage, yet that one person’s life—stolen, beaten down, stripped of freedom—was no less tragic than that of the thousands laboring in Southern fields.

Imagine standing in Getty Square, a place now bustling with commuters and shoppers. Two hundred years ago, that same ground bore the footprints of enslaved Africans—carrying goods, hauling water, serving those who claimed to own them. Picture Central Avenue, South Broadway, McLean—streets now lined with cars and businesses, but once walked by men, women, and children who had no claim to their own futures.

In 1810, the largest slave owner in Yonkers was Augustus Van Cortlandt. He owned 15 human beings. Not land, not livestock—people. The 1820 United States Federal Census reveals familiar names among the city’s slaveholders. Jacob Odell had 17 people in his home, five of them enslaved. Peter Underhill’s house held nine people, two of them slaves. Today, we drive down Odell and Underhill Avenues, never questioning the history behind those names. But should we?

Slavery was not just a man’s business. Women participated, too. Martha Valentine and Hannah Horton enslaved three people between them, proving that the cruelty of bondage knew no gender. According to the New York Historical Society, enslaved people were the backbone of many New York households—hauling firewood, fetching water, cooking meals, cleaning homes, removing waste. They weren’t just laborers; many became skilled artisans, crafting goods that their owners profited from while they remained in chains.

My own ancestors, at least some of them, escaped these shackles. My 5th great-grandfather, Charles Merritt, became a quasi-free Black man in Greenwich, Connecticut. But freedom in name was not always freedom in reality. And even if he was not bound in chains, countless others were. Their pain, their stolen lives, their struggles—those stories still demand to be told.

Yet, today, we find ourselves in an era where people debate whether to call slavery what it was. “Involuntary relocation,” some say, as if rebranding history can erase its horror. Some refuse to discuss LGBTQ+ history. Some refuse to teach about systemic racism. And many others are scared to have an honest conversation about DEI. If we start erasing truth, where does it end? The least we can do—the very least—is acknowledge the history that shaped our city, our country, our present.

Slavery in Yonkers was real. Its echoes remain. And no matter how difficult the conversation– it is one we must have.

Dennis Richmond Jr. lives in Yonkers and is on Twitter @NewYorkStakz. He is a journalist focused on Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ Communities.