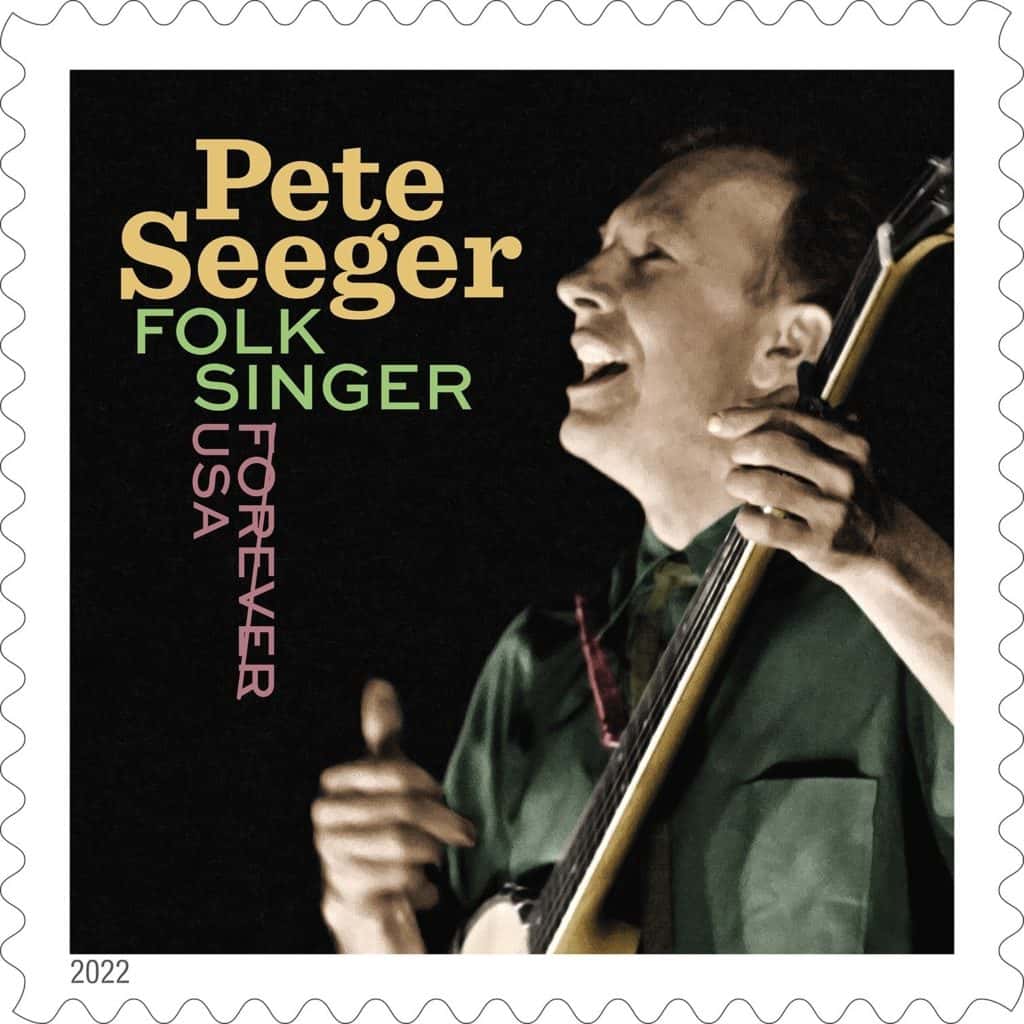

Famed folk singer Pete Seeger was honored as he was inducted into the Postal Service’s Music Icons Forever stamp series at the Jane Pickens Theater.

Share the news of the stamp with the hashtag #PeteSeegerStamp.

“The Postal Service is pleased to present our new Music Icons stamp honoring Pete Seeger, a man who inspired countless musicians and millions of fans around the world,” said Tom Foti, the Postal Service’s product solutions vice president, who served as the stamp ceremony’s dedicating official. “He was not only a champion of traditional American music, he was also celebrated as a unifying power by promoting a variety of causes, such as, civil rights, workers’ rights, social justice, the peace movement and protecting the environment.”

The other participants at the stamp ceremony were members of Seeger’s family; Chris Funk, music director of the Newport Folk Festival Presents For Pete’s Sake; and Béla Fleck, who performed the national anthem.

The Pete Seeger Forever stamps are being sold in panes of 16.

The stamp art features a color-tinted, black-and-white photograph taken in the early 1960s by Dan Seeger, the performer’s son. Pete Seeger is shown in left profile, singing and playing his iconic banjo.

The square stamp pane resembles a vintage 45 rpm record sleeve. One side of the pane includes the stamps and the image of a sliver of a record seeming to peek out the top of the sleeve. A larger version of the stamp-art photograph appears on the reverse side with the words “Pete Seeger FOLK SINGER.”

Art director Antonio Alcalá designed the stamp and pane. Dan Seeger’s photograph was color-tinted by Kristen Monthei.

The Forging of a Folk Hero

Pete Seeger (1919-2014) revived and championed traditional American music. A resolute voice of conscience and defender of American liberties, he adapted and popularized the song “We Shall Overcome,” which rose to become the predominant anthem of the civil rights movement. His own compositions galvanized populist uprisings: “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” has given musical voice to peace movements since the Vietnam War, and “If I Had a Hammer” has been embraced by an array of activists.

“It is an honor to see a photo of my father I’d taken some 60 years ago become this wonderful Forever stamp,” said Dan Seeger. “My dad did most of his correspondence by hand — written letters — and I can imagine him smiling and of course appreciating this great honor because he relied on the U.S. Mail with its simplicity and honesty, knowing that thoughts and ideas can go from the sender over a tremendous expanse to a single receiver and get delivered.”

Responding to Seeger’s enormous charisma as a performer, audiences turned his concerts into sing-alongs, led by his clear tenor and ringing five-string banjo, its head inscribed: “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.” In the eyes of generations of admirers, Seeger’s ideals and ordeals elevated him from folk singer to folk hero.

He was raised in New York and Connecticut by musician parents. Young Peter Seeger intuitively took to any musical instrument put within his reach. While he was still a toddler, his family made a pilgrimage to the South — homemade trailer in tow — to introduce classical music to the people of Appalachia. Following a recital by Seeger’s parents, the teacher-student balance quickly reversed; audience members gave an impromptu concert of regional folk tunes. A return to the South during his teenage years further enticed Seeger. Rural Southern folk music — and the five-string banjo that characterized it — would influence his long, extraordinary career.

Seeger dropped out of college after two years at Harvard University, where he had prioritized populist causes and music over academics. In the late 1930s, he moved to New York City and also worked in Washington, DC, where he archived folk songs and recordings for the Library of Congress. He also hitchhiked and hopped boxcars to see America and hear its music. During these youthful wanderings, he met influential folk musicians, including Huddie Ledbetter, best known as Lead Belly, and Woody Guthrie, who penned “This Land is Your Land” at around the same time. Guthrie and Lead Belly became two of Seeger’s mentors.

Seeger and Guthrie roamed the country and organized the Almanac Singers, a loose coalition of musicians who tunefully promoted labor unionization wherever they went. Staunchly anti-fascist, the Almanacs wrote patriotic songs as Hitler menaced Europe and America entered World War II. Drafted in 1942, Seeger served three years in the Army, entertaining troops stateside and in the South Pacific until the Allied victory.

After the war, Seeger formed the Weavers, a quartet of like-minded musicians. They did not anticipate huge mainstream success, but it arrived quickly: “Goodnight, Irene,” a Lead Belly composition that was the flip side of their first release, became the number one song of 1950. This surprise hit was followed by other catchy releases. Some, such as “Wimoweh,” and in later years, “Guantanamera,” were imported gems that Seeger plucked from obscurity. “Michael Row the Boat Ashore” and “On Top of Old Smokey” were among the songs from Americana that he repopularized. Still others, such as “The Hammer Song (If I Had a Hammer),” were written or co-written by Seeger, with the catchiness and thematic qualities of folk anthems.

The Weavers’ success was meteoric and their downfall just about as swift. The group’s left-wing politics did not sit well with Congressional anti-Communist crusaders during the early Cold War era. Disc jockeys stopped playing Weavers records, their bookings dried up, and they disbanded in 1952. They would regroup a few years later, but they would never regain the same widespread popularity.

Subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955, Seeger was asked whether he had sung for Communist groups. Defiantly, he called such questions improper, and asserted his patriotism and his right to sing to anyone who wanted to hear him. His lack of contrition brought him 10 counts of contempt of Congress, each carrying a one-year prison term, a sentence not overturned until 1962. Although not imprisoned as the legal process played out, he was effectively blacklisted. Media executives were intimidated by the consequences of association with those branded subversive, and Seeger would not appear on network television again until 1967.

He was sidelined but couldn’t be silenced. Seeger recorded prolifically, embarked on a musical world tour with his family, sang with civil rights groups in the Deep South, and virtually invented the college campus concert circuit.

During Seeger’s exile from radio and TV, the seeds he had sown for a folk revival bore ample fruit for other artists. The Kingston Trio had a hit record with “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” as did Peter, Paul and Mary, who also charted with “If I Had a Hammer.” The Byrds electrified “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” a beautifully simple song that Seeger had adapted from a favorite biblical passage. That record topped the charts in 1965. Seeger also fostered the careers of a new generation of folkies, including Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, partly through his early stewardship of the Newport Folk Festival.

In 1963, Seeger garnered some radio airplay with his biggest solo hit, “Little Boxes,” a song satirizing the conformity in “ticky-tacky” housing developments proliferating across the post-war American landscape. Although the song’s popularity ended his long radio silence, Seeger remained motivated not by hit records but by the unity and harmony of voices lifted in purposeful song.

Classrooms were among his favorite venues. In time, the school kids he had sung with in the 1940s and ’50s grew into the politically empowered college students of the 1960s. As the civil rights and anti-war movements gathered steam, Seeger was often present on campuses to offer his talents and support.

Having taken a stand in so many of the 20th century’s pressing societal issues, Seeger found his next cause in his own backyard. Sailing near the log cabin he built with Toshi, his longtime wife and partner, he became alarmed by sewage, garbage and chemical runoff in the Hudson River. To call attention to the river’s plight, he spearheaded efforts to build a sloop like the tall-masted wooden cargo boats that had sailed the Hudson in centuries past.

Called Clearwater, the vessel was launched in 1969 and ever since has brought attention to the river through onboard concerts, education programs and riverside festivals. Now a National Historic Site, the sloop Clearwater and the organization supporting it have inspired generations of river stewards, and other environmental groups have emulated its organizational model.

Seeger was widely honored during the later years of his life, winning both the National Medal of the Arts and the Kennedy Center Honors in 1994. In 1996, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. His album “Pete” won the 1997 Grammy Award for best traditional folk album, an award he also won in 2009 for “At 89.” New audiences were introduced to Seeger’s music when Bruce Springsteen devoted an entire 2006 album to Seeger songs.

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at a concert marking the 2009 presidential inauguration of Barack Obama, Seeger, along with Springsteen and a crowd of some 400,000 people, sang “This Land is Your Land.”

While Pete would be proud of the postage stamp in his memory, he would not be happy to learn that the Westchester concert that helped raise funds for his beloved Clearwater Sloop and to clean up the Hudson River is no more.

“Dear Friends, We’re sorry to announce that we will not be holding a 2022 Clearwater Festival. However, our organization has recently passed a strategic plan, and we are determined to re-envision the Clearwater Festival for future events. You may read the full story here. We hope that you will continue supporting our year-round environmental education and advocacy work on the Hudson River,” wrote the organization.

The festival, usually held over Father’s Day weekend at Croton Point Park in Croton on Hudson, was originated to help raise funds to build the sloop Clearwater, a boat which raised awareness to clean up the Hudson River in the 1960’s and 70’s.

The festival was one of the original environmental music concerts, and grew from a simple “folk picnic” as Pete used to call it. For those of us who attended with our fathers almost 50 years ago, we hope that Clearwater can raise the funds to make sure this important event, which educates and inspires generations to help protect the Hudson River, which Pete worked to clean up.