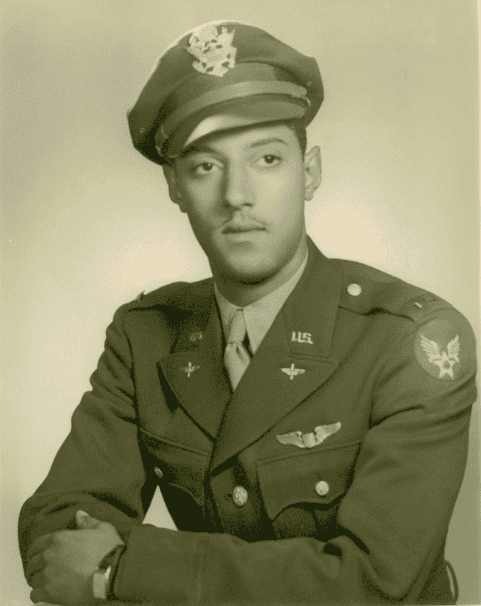

2nd Lt. Ivan McRae, 477th Bombardment Group

By Yonkers Historian Mary Hoar

Born in Harlem in 1923 to Jamaican natives Ivan Sr. and Laura McRae, Ivan Jr.’s family moved to Yonkers and Runyon Heights just a few years later. While attending School One, he was active in Boy Scout Troop 34, receiving multiple merit badges and awards; he later assumed the role of Assistant Scout Master. While in School One, he took part in class activities and programs, portraying a variety of roles, including lawyer in a tribute to Abraham Lincoln.

Ivan graduated from Roosevelt High in 1941; after graduation, he assumed the post of Assistant Scoutmaster of Troop 34, his former troop. When Yonkers Post 68, Jewish War Veterans, presented his troop a parade flag at a special ceremony held at the Nepperhan Youth Center, McRae was given the honor of accepting the flag.

While attending Columbia University, he worked for the NY Central as a part time baggage porter at the Harmon Station. According to an interview his granddaughter published online many years later, he was on duty when he heard a loud commotion in the waiting room; he ran upstairs to investigate and learned about the attack on Pearl Harbor.1

He enlisted in the Army’s Aviation Cadet Program, and in 1943 was chosen for Pilot Training at Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama.

At 6’1”, he was too tall to fit in a fighter plane; this limited his options. Instead, he earned his wings as a Twin-Engine Bomber Pilot (Class 44-J-TE) with the famed Tuskegee Airmen and flew B-25s.

McRae was attached to the 477th Bombardment Group; they were assigned to Freeman Field (Indiana) March 1945 under command of Colonel Robert Selway, who created two clubs for officers. McRae and the other officers in his company were directed to use the Non-Commissioned Officers Club and forbidden to use the “Supervisory” Club, although lower ranked White officers were welcome there. In a carefully organized non-violent protest, later labeled the “Freeman Field Mutiny,” Black officers tried to enter the officers’ club five at a time April 1945; they were confronted by military police and arrested.

Within a few days, sixty-one Black officers were arrested, charged with “disobeying a superior officer.” The charges were dropped against all but 3 officers who were charged with using “violent activity.” A few days later, Selway issued Base Regulation 85-2, which dictated which facilities they could use… and required all to sign the order and obey it.

One hundred-one Black officers refused to sign and were arrested. They were flown to Godwin Field and placed under house arrest. About a month later, the War Department determined Selway’s Base Regulation 85-2 violated the Army’s existing code. A few months later, the three officers accused of “using violent activity” were court-martialed; the decision was reached July 1945.

Two men were exonerated, and the third got a very light sentence. Reprimands were removed from the other arrested officers’ records, if they requested removal. Not all wanted them removed, considering their courageous stand against injustice a badge of honor.

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr. took over command of the unit; for the first time, McRae’s 477th Bombardment Group was led by Black officers. Although McRae returned to training to fly missions in the Pacific, the August 1945 end of World War II spared Second Lieutenant McRae from combat.

After the end of the war, McRae returned to Columbia University to finish his studies via Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (the GI Bill); this gave returning servicemen money for education and housing to help them readjust to civilian life.

On graduation from Columbia University’s School of Engineering in 1948, he was awarded the prestigious Darling Prize, an annual monetary award given to “the most faithful and deserving student of the graduating class in mechanical engineering.”

A few months after graduation, McRae married Marjorie Cox. The couple settled on Long Island, raising their four children in Dix Hills. McRae worked for defense industries, for companies such as Fairchild Space and Defense Systems.

On July 26th, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, ending desegregation; it ordered full integration of all branches of the US military. It stated, “ It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible… There shall be created in the National Military Establishment an advisory committee to be known as the President’s Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services,”3 The Committee’s mission was to review and change military regulations to facilitate integration in the service.

Congress awarded the Tuskegee Airmen their highest honor, the Congressional Medal of Honor. This medal was presented to acknowledge and appreciate their “unique military record, which inspired revolutionary reform in the Armed Forces.” Designed specifically to honor the Airmen, the medal portrays three Tuskegee Airmen—a pilot, a mechanic and an officer. It also depicts the three planes the Airmen flew, the B-25, the P-40 and the P-51.

McRae received his medal in 2010 from Congressman Steve Israel, presented at a special ceremony at the American Airpower Museum in East Farmingdale. Israel also presented him with an American flag flown over the US Capitol in honor of Second Lieutenant Ivan McRae, Jr.

McRae passed away six years later at the age of 93 and was laid to rest in Calverton National Cemetery.