Westchester organizations, community members join ceremony to remember lost fight for tribal sovereignty

By Zach Youngerman

How do we honor and understand the sacrifice of those killed? That was the question for the crowd gathered on August 31st at a Van Cortlandt Park monument to honor Wappinger and Mahican warriors killed by British soldiers in the American Revolution.

The event was organized by the Daughters of the Revolution (DAR), the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), the Kingsbridge Historical Society and “local community members who wish for the historical legacy of Chief Daniel Nimham to be preserved,” according to the event program. Representatives from the Town of Fishkill and the New York City Parks Department also spoke.

The ceremony mixed American military rituals with Native rites, including a sage smudging, a folding of the U.S. flag, and a dedication with stones from across the former Wappinger homeland. The DAR led the Pledge of Allegiance; Dr. Janice Turner of the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware spoke a Lenape invocation.

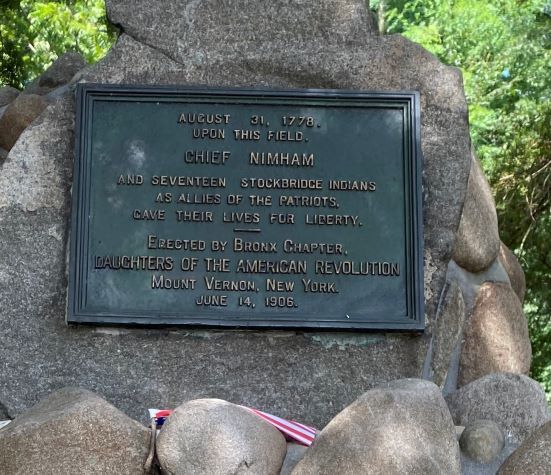

That inclusivity would not have accompanied the original dedication of the monument. It was the DAR – not the descendants of the Native soldiers – who had the power in 1906 to place a privately-funded monument in a New York City park. Native Americans hadn’t even been granted U.S. citizenship yet. It is only recently that they have felt safe to “be out,” shared Oleana Whispering Dove, a curator of Native American programs and an Eastern Tsalagi-Algonquian descendant who participated in the ceremony. And yet, that the battle and Sachem Nimham are known popularly is perhaps due to that modest hundred-plus-year-old plaque.

In late summer 1778, Wappinger Sachem Daniel Nimham, a statesman, and his son Captain Abraham Nimham led an “Indian Corps” with Native soldiers who had served in the Continental Army. Patrolling in today’s southern Westchester and north Bronx on August 31, the militia was ambushed by General Simcoe. They fought the British to death rather than retreat. The plaque in Van Cortlandt Park describes them as martyrs, “allies of the patriots gave their lives for liberty.”

Although the Wappinger were allies with the American colonists, sovereignty, not liberty, was their aim. Before fighting in the War, Daniel Nimham fought for years in the courts for Wappinger property rights. He even traveled to London, obtaining a favorable recommendation from the Lords of Trade in a case against the wealthy Philipse’s for hundreds of thousands of acres. Despite those orders from England and a patently dubious legal claim of the Philipse’s, the court in New York decided that “admitting such Kind of Complaints…[Will] open a Door to the greatest Mischiefs.” In other words, an unraveling of all colonial property rights. Made landless, the Wappinger peacefully left their homeland to join Mahican allies settled in a missionary reservation called Stockbridge in Massachusetts.

However, the Wappinger saw a strategic opportunity to regain their land when opposition to British colonial rule grew in the mid 1770s. They joined the Americans and fought from Bunker Hill to Fort Ticonderoga. And while the colonists’ ultimate victory won them a new nation, the Stockbridge Indians’ sacrifice was not rewarded. New York State’s Commissioners of Forfeiture did seize, redistribute and auction loyalist property, including land of the Philipse’s, but none was returned to the Wappingers. Nor did widows and orphans of the Stockbridge Militia receive the military pensions their White peers did. Instead, settlers moving to the Berkshire valleys took over the Stockbridge government and pushed out the remaining Native Americans, who moved to Western New York, and eventually Wisconsin.

Joan Barnes of the DAR memorialized that displacement, reading a prayer “This Land Belongs to No One” that includes the following

We acknowledge the history of pain, disease, and bloodsheds native peoples endured when they were colonized…Let us honor the memory of those who died on this land, who lost their sovereignty. Let us honor the native people who to this day keep their sacred traditions and culture alive and seek to reclaim, reassert, and revive their sovereignty.

That reassertion is happening in many ways. A Daniel Nimham Intertribal Pow-Wow has been held for 20 years. And a Native “land back” movement is growing. In 2019, the Presbytery of Hudson River transferred church property in Stony Point back to the Ramapough-Lenape Nation.

Whether land will be returned to the Stockbridge-Munsee is far from certain. For now, another memorial will have to suffice. This fall, the Town of Fishkill will unveil a sculpture of its truly native son, Daniel Nimham, expanding in form and meaning the existing plaque that honors him for “defending the American cause.”