Editor’s Note: City of Yonkers Historian Mary Hoar, recently gave a presentation at Pressley Memorial Church on forgotten and accomplished African Americans who made a difference in Yonkers. Here are a few that we remember.

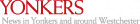

Forgotten by history is Yonkers resident John Edward Bruce, a prolific journalist, historian, writer, orator, civil rights activist, Prince Hall Mason and Republican. Bruce lived in Yonkers for almost 20 years. Born in Maryland, Bruce’s mother Martha escaped to Washington a year after his father was sold. While in DC, he was given the advantage of a private education by his mother’s employer; he was taught by Belva Bennett Lockwood, who twice ran for US President on the Equal Rights ticket.

Bruce joined the staff of the NY Times Washington office, working with Republican abolitionists, and later was the Washington correspondent for papers in London, Richmond, St. Louis, Chicago, New York, North Carolina and Detroit.

He founded several African-American newspapers throughout the east coast. After he moved to Yonkers, he established the Weekly Standard in 1908; articles from this well written newspaper often were reprinted in the other area papers.

He joined the AME Zion Church on New Main Street, and founded the Sunday Men’s Club, creating a group of local intellectuals, bringing in speakers and cultural programs on topics relevant to the life of African Americans.

Bruce was a respected community leader in Yonkers. An active Republican, he served on many committees, and was on the dais at most Republican Party rallies. A member of the Yonkers Day Citizens’ Committee, he was tasked with welcoming NY Governor Whitman. Although a Republican, he served on the General Inaugural Committee for President Elect Wilson’s inauguration, Chairman of the Committee on Public Comfort.

In 1911, Bruce founded The Negro Society for Historical Research with his mentee Arturo Schomburg in the Bruce living room at 146 Warburton Avenue. Their aim was to create an institute to support creation of a comprehensive lending library of books on Black history and philosophy. After Bruce’s death this library became the foundation of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York repository for information on people of African descent worldwide.

As typical of many talented people, Bruce’s literary work did not support his family. He obtained a position with the Customs House in NYC; as his health became more of an issue and his commute more difficult, he moved to Brooklyn to be closer to work.

At the time of Bruce’s death in 1924, he had three funeral services; well over 5,000 people marched behind his hearse as it proceeded between services. Prince Hall Masons and members of the Universal Negro Improvement Association were prominent members of his funeral processions, marching in their uniforms. UNIA founder Marcus Garvey dressed in black to symbolize the grief of the organization and community.

Bruce returned to Yonkers, and is buried in an unmarked grave in Oakland Cemetery.

Tuskegee Airman Lee Archer

Are you familiar with arguably the most famous Tuskegee Airman, Lee Archer? He was born here in Yonkers, at 96 Woodworth Avenue! During his years in Yonkers, one of Archer’s favorite pastimes was reading comic books about World War I flyers. His family later moved to New York.

Archer left college to enlist in the Army Air Corps in early 1941 but was rejected for pilot training because the military didn’t allow Blacks to serve as pilots. After the Tuskegee program officially began, Archer re-applied and entered the Army. He was accepted into aviation cadet training several months later, and reported to Tuskegee Army Airfield. Archer graduated number one in his class, and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant July 28th 1943.

A pilot in the 332nd Fighter Group, Archer is best remembered for his exploits of October 12, 1944. In the midst of a furious series of dogfights over German-occupied Hungary, he shot down three Hungarian fighter planes within 10 minutes.

Archer went on to fly 169 missions over 11 countries in the “Ina, The Macon Belle,” his red tail P51 Mustang named for his girlfriend and later wife, Ina Burdell.

After he retired from the Air Force in 1970, he went to work for General Foods, becoming the company’s first Black Vice President.

In 2009, he served as advisor for the George Lucas film Red Tails, a story based on the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.

He passed away in 2010 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

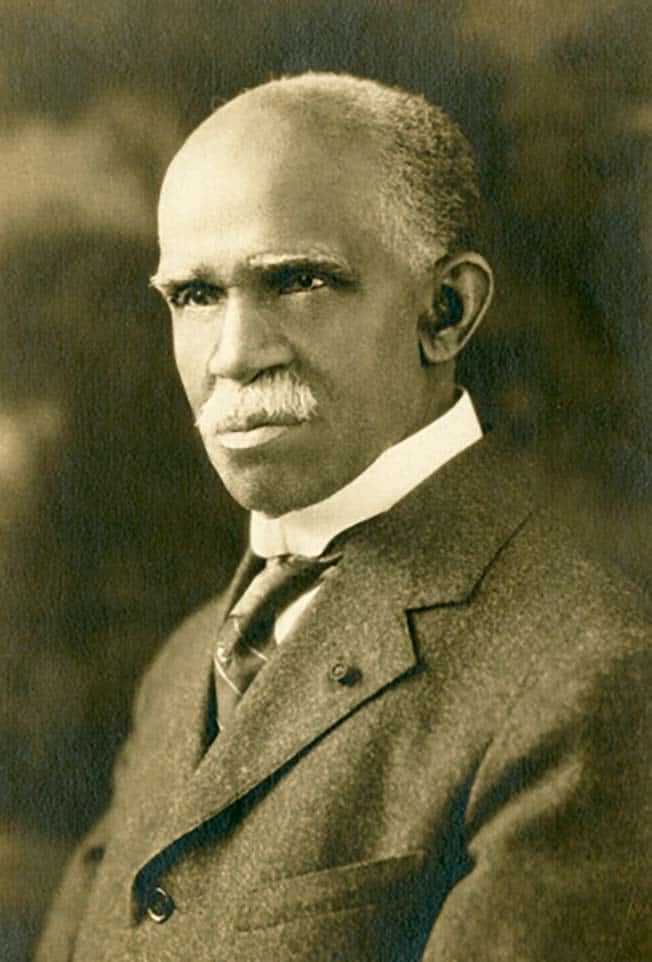

Francis Moultrie

Yonkers first successful caterer was Francis Moultrie, pictured above, arguably one of our most respected African American citizens in early 20th century Yonkers. Born in South Carolina, he was determined to make a better life for himself, with a dream of opening a catering business. He believed Yonkers was the place to achieve this dream.

Employed to work as a butler four days after he arrived in 1869, his careful saving helped him achieve his first dream; he returned to Charleston to marry his fiancé Fannie Alston. Returning to Yonkers, he was offered a job at Washburn & Company, the largest hardware store in Yonkers.

His last position was at Acker Edgar & Company; owners of that company, impressed with his skills, encouraged Moultrie’s dreams. He opened a restaurant and catering business in 1878 on Dock Street.

The business took off, and Moultrie wanted to expand. He was unable to get a business loan, a lesson he did not forget. The couple’s hard work and work ethic grew the business. He opened a store in the Warburton Building next to Philipse Manor Hall, and featured French and American cuisine. His specialty? Ice Cream!

Religion was important to Moultrie; two years after arriving in Yonkers, in 1871 he was one of the founders of the first African-American church in Yonkers, Memorial AME Zion Church. He served as its president until his death. He frequently preached at the church and was known for his witty stories.

Francis Moultrie was extremely active in the Republican Party, served as President of the Colored Republican Club and on Yonkers Republican Central Committee for several years. Remembering his trouble getting a bank loan, he founded a bank,. He founded the Ethiopian Life Insurance Company, the first African American life insurance company.

Another Moultrie first? In 1904, Moultrie founded the Colored Co-Operative Company of Yonkers incorporated with capital of $50,000. Their purpose was to build fourteen multi-family houses on Culver Street to provide African Americans decent housing, as too many landlords only rented substandard housing to Blacks. In less than a year, similar companies were formed in Poughkeepsie, Troy and Tarrytown, thanks to the success of Moultrie’s plan.

Moultrie was so successful, he was included in Booker T. Washington’s book The Negro in Business as one of the country’s most successful businessmen.

At the time of his death in 1915, he was universally mourned. The Yonkers Herald wrote after his death,” With the passing of his life, goes the the living evidence of one who showed that color makes no difference in making one’s way in the world, if but the desire to do so is only there.” He was laid to rest in St. John’s Cemetery.

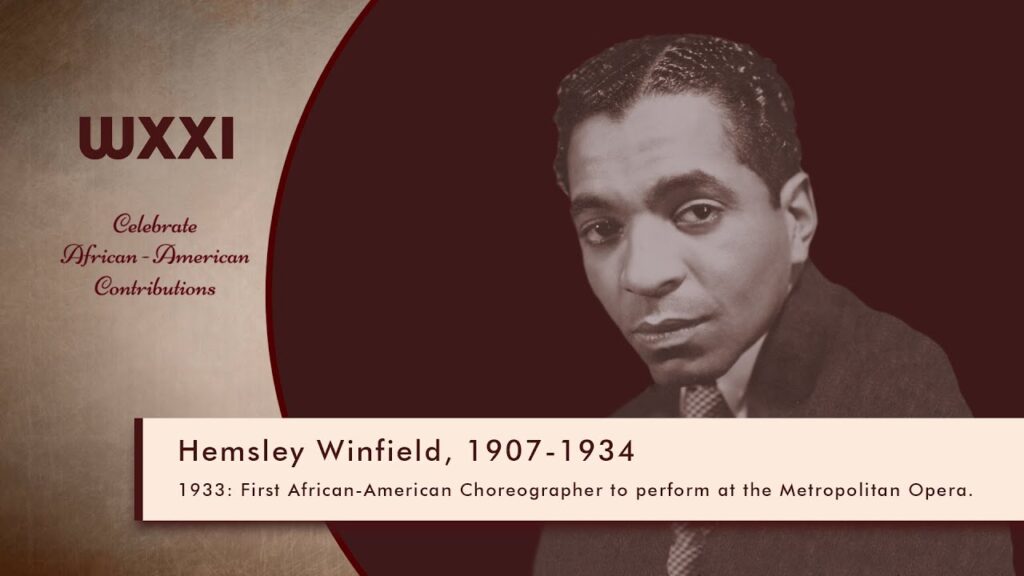

Helmsley Winfield

Yonkers native Helmsley Winfield was the father of African American Modern Dance! He was born and grew up on Wolfe Street off McLean Avenue, and graduated from School 13, where he was president of his eighth grade class and a star athlete.

At the age of 18, he founded and directed the Sekondi Players of Yonkers (1925). The company gave its first performance on March 6, 1931, at Saunders Trade School, a benefit for Yonkers’ unemployed. Originally called The Bronze Ballet Plastique, Winfield soon changed the name to The New Negro Art Theater Dance Group.

In 1933, the company appeared in the premiere of The Emperor Jones at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Winfield took on the role of Congo, The Witch Doctor; he was the first African American to sign a contract with the Met and the first African American to have his name in the program; the New Negro Art Theater Dance Group was the first Black company to perform at the Metropolitan Opera.

He performed in New York, then joined the traveling company, dancing the role in Brooklyn, Philadelphia and Baltimore. Hemsley’s performance was reviewed as “a thrilling exhibition of dancing.”

Winfield constantly was working, concerned about supporting his company, literally working himself to death. Hemsley Winfield, the pioneer in African American concert dancing, died of pneumonia shortly before his 27th birthday. He is buried with his family in an unmarked grave at Oakland Cemetery.